It's Friday night in the heart of Detroit at the Red Bull House of Art, a 14,000-square-foot underground art gallery carved out of the basement of a

19th century brewery. Thousands of the young, the chic and the smart have gathered to celebrate

a new cycle of local artists’ work. DJ Erika is spinning, champagne is flowing. Outside, a line of people

hoping to enter winds around the block.

Christopher Stevens, a good-looking 29-year-old car designer from

California, is the host of the hottest after-party, in his loft above the brewery's back stairs. In the middle of the room casually rest two of his motorbikes, with a piano in one corner. Darko,

the resident pit bull puppy, darts in between guests from one end of the room

to the other.

“I love Detroit,†Stevens says, after declaring how

depressing he finds the idea of suburbs. “Detroit is full of heritage and

history. I came for its grittiness. It’s full of culture â€" old Americana

culture.â€

To

Kirk Cheyfitz, CEO of New York-based advertising firm Story Worldwide, and a

former Detroit Free Press award-winning reporter, companies coming to the Motor

City for branding are “wrapping themselves around a mythology that is

outlawâ€.

“It is a safe way to be appealing to young people all over

the country who embrace those kinds of feelings â€" of wanting to be outside of

the mainstream while actually defining the mainstream,†Cheyfitz says.

Those wanting to live

on the edge in Detroit might walk just a couple of blocks north-east of the Red Bull House of Art. There, after

a bitterly cold winter, a few squatters have moved back into the tagged,

abandoned buildings surrounding a former industrial railroad. The

crumbling,

urban ruins are just part of the landscape in a city where an estimated

78,000 structures

are no longer formally occupied. Crime is part of that landscape; police chief James

Craig went on record this year telling “good

Detroiters†to arm themselves with guns against criminals and home

intruders. It's a city where the homicide rate continued to take

number one spot ahead of other large American cities in 2013, including

Chicago. The median

household income in Detroit was just $23,600 a year in 2012.

Detroit's once glorious and now decrepit Michigan Theatre has been saved from the wrecking ball by being transformed into a car park. Photograph: Mira Oberman AFP/Getty Images

Detroit's once glorious and now decrepit Michigan Theatre has been saved from the wrecking ball by being transformed into a car park. Photograph: Mira Oberman AFP/Getty ImagesYet, to an advertiser's eye,

Detroit is

cool. Gritty. Tough. Resilient. Authentic in its struggle. True in its

American spirit of

hard, honest work, ruins and all.

That's where it gets uncomfortable for Detroit, The Brand. Detroit, the American phoenix rising from the economic ashes, is sitting on a valuable natural resource: street cred. This has not escaped the notice of profit-driven companies see the city's rebirth as a chance to brand

themselves and sell authenticity.

The airwaves and billboards are plastered with ads from Chrysler (a

Detroit native), Redbull (from Austria), new vodka brand from the giant

French Pernod Ricard group, Our/Vodka, and luxury watch and bicycle

company

Shinola. They present a romantic, nostalgic take on grit â€" a highly effective spin, which presents poverty and urban decay as cool. The nostalgia element is all the more evident in that ads by Shinola,

Redbull and Our/Vodka are often filmed in black and white.

Shinola’s spot features bike riders and a beautiful, blonde,

white female model hugging a (presumably local) young, black girl. Redbull’s spot

aired during this year’s Grammy Awards features local artist Tylonn Sawyer

telling a compelling story of beauty and resilience. Our/Vodka’s launching ad

includes Detroit’s beautiful, eerie, abandoned Michigan Central Station, stating

the brand is rooted in “people†and “communityâ€.

These are brands that Detroiters, even the hip newcomers, likely can't afford. It's hard to imagine that many in Detroit could afford a $1,950 bicycle

or a $900 watch, irrespective of whether or not the latter now comes with a

lifetime warranty.

The city's poor would not be able to afford it anyway

Our/Vodka, a new micro-distilled vodka

brand currently being launched by French alcohol giant Pernod Ricard, is

actually seeking to invest in the people of Detroit, its CEO and global brand manager

Åsa Caap, says. Caap, who “fell in

love†with the city when she first visited it, says she has been approached by other foreign companies curious to know

whether investing in Detroit has been a positive experience. She has always said yes.

Our/Vodka’s business model is to be a global brand with

local roots, the name changing according to the city it is being housed out of:

in Detroit, it will be known as “Our/Detroitâ€. Three local partners who have

been taken on to manage the distillery and bar where the vodka will be made and

produced will retain 20% of profits.

Standing in the building where the Our/Detroit distillery

and bar will open this summer, near the famous abandoned

Michigan train station, Caap says she realized bringing vodka to a city facing

such socioeconomic woes could be seen as a problematic temptation, but she was reassured

that the high prices of the vodka her team was introducing meant that many of

the city’s poor would not be able to afford it anyway.

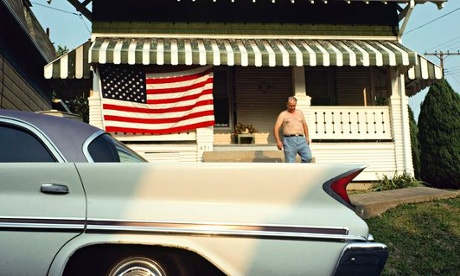

Nostalgia taken centre stage in Chrysler ads and Detroit's rebranding. Photograph: Nathan Benn/ Nathan Benn/Ottochrome/Corbis

Nostalgia taken centre stage in Chrysler ads and Detroit's rebranding. Photograph: Nathan Benn/ Nathan Benn/Ottochrome/CorbisIt was Chrysler that kicked off the vogue for Detroit nostalgia. Kicking off the trend in 2011 was Chrysler’s Super Bowl “Born

of Fire†ad featuring Eminem. The unapologetic commercial, featuring sleek new cars, did not seek to cover

up the city’s collapse. Instead, it embraced it.

“What does a town that’s been to hell and back know about

the finer things in life?†The spot’s male voiceover asked. The answer came

back as hopeful as it was tough. “It’s the hottest fires that make the hardest

steel.â€

In post-recession America, and with Chrysler itself just

coming back from the dead after a government bailout, the Detroit-centric

narrative was gripping, and proved a huge sales success. Detroit the city has

been at the center of Chrysler publicity ever since.

'Detroit is a brand unto itself'

“In this day and age, it becomes important for brands to

make sure they tell an authentic story,†says Detavio Samuels, Detroit

president of Glabalhue, the advertising firm behind this year’s Chrysler Super

Bowl ad featuring Bob Dylan as well as the city of Detroit at its core. Samuels

says audiences are hungry for transparency after decades of spin.

“People are looking for values that corporations have that

they can connect to,†Samuels says.

For Shinola, a new brand of old-fashioned luxury watches and

bikes, which opened flagship stores in Detroit’s Midtown, as well as New York’s

Tribeca in the summer of 2013, choosing to place headquarters and assembling

activities within the eight-mile confines of the city of Detroit was fundamental to

the company’s makeup and branding strategy.

Steve Bock, Shinola’s CEO, who spends a majority of his time

working out of the Motor City, says Detroit is a globally recognized “brand

unto itselfâ€. And the recognition is not due to its status as America’s largest

city ever to go bankrupt. Far from it.

Globalhue's ad featuring Bob Dylan and Detroit.

“It’s a city that is built on heavy manufacturing and the

automobile industry. There is that face, there is that history and that

heritage.â€

Shinola’s three-pronged marketing campaign has focused on (mostly

Detroit-based) American workers, the city as a brand and quality

craftsmanship. Out of 300 or so current employees, Shinola says it currently employs

around 200 in Detroit, with new recruits ongoing.

As it stands, Shinola’s strategy has paid off. According to

its own data, it generated $20m in sales in its first six months of

business, with revenue expected to reach $100m in 2017.

While Bock remains humble about the company’s impact on the

city’s economic affairs, he declares that Shinola sees itself as “a small part

of what we think will be a great future for the cityâ€.

But if the brands are using Detroit and its communities to

brand themselves, how rooted are they really â€" especially if their products are

aimed at projecting an image of saving Detroit's people rather than serving them?

The idea of saving Detroit does not just carry a

socioeconomic connotation to it, it also carries a deeply racial one,

recalling a painful, segregation-burdened past. White populations once

fled the city, but are now coming back where they see opportunity. After

decades of white flight, Detroit today is 82.7% African American, with

many of its surrounding suburbs overwhelmingly white and starkly richer.

Grosse Pointe, which stands just to the east of the city limits, is 93%

white with a median household income of $103,867.

As much as outside investment and an alternative narrative

are needed to get the city back on its feet â€" and raise its desperately low tax

base â€" some argue companies using the city’s brand may be getting more out of

it than they are giving back.

A vacant home in an east side neighbourhood of Detroit. Photograph: Rebecca Cook/Reuters

A vacant home in an east side neighbourhood of Detroit. Photograph: Rebecca Cook/Reuters“The

economic impact of the Detroit brand on the material conditions of the

residents of the city is limited at best,†says Bruce Pietrykowski, a professor

in economics at the University of Michigan, who specializes in labor,

industrial relations and urban political economy.

“What

is important to mention is the way in which profit-making ventures â€" in some

cases the very manufacturing firms that devastated the local economy â€" seek to exploit the image of de-industrialization, rebrand it as grit

and determination, and use it to sell products at a mark-up.â€

Indeed,

while Shinola’s marketing explicitly evokes a time when industries produced

their goods at home, when skilled, manufacturing, often unionized jobs

presented solid pathways to the middle class â€" those times, along with

America’s economic structures, have most certainly, and irrevocably changed.

Shinola jobs are non-union, and starting salaries average around “$12 or $13 an

hour†according to Bock, way above the minimum wage, but certainly not in the

same bracket as the middle-class, Ford-type union protected jobs the company is

trying to evoke through marketing.

To

great fanfare this March, Shinola donated four giant $12,000 clocks to

the city, scattering them around select Detroit neighborhoods. It only

took a few hours for reports to emerge that one of them had been tagged.

And while Shinola was swift to send a team out to repaint, the act of

vandalism seemed to briefly speak to strange, and sometimes tense times

in the Motor City.

http://www.theguardian.com/money/2014/may/14/detroit-bankrupt-brand-ad-chrysler-nostalgia

No comments:

Post a Comment